WHAT LINKS THEM?

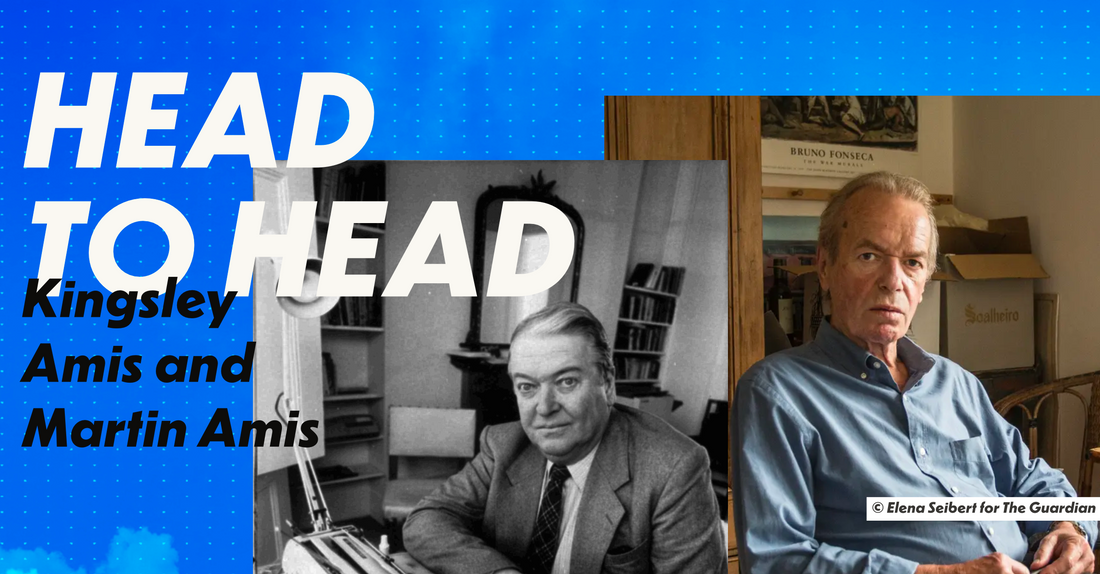

Kingsley

Born in 1922, Kingsley Amis, father of Martin, was an Oxford-educated comic novelist whose work satirised the social changes that England went through after the Second World War. His first novel, Lucky Jim (1954), won the Somerset Maugham Award, universal acclaim, and propelled him into international stardom. His protagonists are memorable anti-heroes whose bad behavior masks their struggle to find meaning in a post-war world. He is often described as the defining novelist of his generation.

Martin

Born in 1949, Martin Amis, son of Kingsley, is an Oxford-educated comic novelist whose work satirizes the social changes that England has gone through since the Second World War. His first novel, The Rachel Papers (1973), won the Somerset Maugham Award, universal acclaim, and propelled him into international stardom. His protagonists are memorable anti-heroes whose bad behavior masks their struggle to find meaning in a post-war world. He is often described as the defining novelist of his generation.

WHAT DIVIDES THEM?

Kingsley

Kingsley’s anti-heroes are likeable. Their bad behavior is understandable; they rail against the uptight tea-and-biscuits culture of 1940s’ Little England and we cheer them on. James Dixon, in Lucky Jim, for example, is forced to spend a weekend in an upper-class English family’s country manor. Their snobbish passive aggression exasperates him and, to their horror, he escapes to the pub. Happier smoking and drinking and laughing than negotiating the rituals and customs that govern the family’s repressed and outmoded world of cucumber sandwiches and madrigals (a world familiar to readers of the English novel), Dixon is refreshingly improper. Kingsley Amis’s anti-heroes are people like us.

Martin

Martin’s anti-heroes are repulsive. They indulge in every excess available to them: they are never not taking drugs; never not sleeping with strippers and prostitutes; never not exploiting someone. In Money, for example, the Thatcherite badboy John Self reels off a litany of sordid excesses with wicked pride as he boasts to the reader about just how much money he has and just how irresponsible is his spending of it. His vertiginous debauchery is nauseating – the (sensible) reader wants nothing to do with him or his lifestyle – yet the immoderation is mesmerizing. As the writer Carl Hiaasen has said, “he pushes you right to the edge of unease and discomfort and it’s beyond cringe-worthy. It makes you shudder. And yet you keep reading.”

WHAT DID THEY THINK OF EACH OTHER?

Kinsley

According to Martin, his father does not have a very high regard of his work: “I can point out the exact place,” he once said, “where he stopped and sent Money twirling through the air; that's where the character named Martin Amis comes in. ‘Breaking the rules, buggering about with the reader, drawing attention to himself,’ Kingsley complained.” Certainly, Kingsley has publicly denounced aspects of his son’s writing – he hated his postmodern games and described his politics as “a lot of dangerous howling nonsense”. And it is true that in a letter to the poet Philip Larkin, he once described Martin as “a fucking fool”. But harsh words are always followed by expressions of love: “I admire him very much as a man,’ he once said, “I regard him as one of my best and closest friends.”

Martin

Martin is less publicly outspoken about his father, but his writing presents a fierce challenge to everything he stood for. Kingsley was a staunch realist, who hated the kind of Modernist novelists operating before the war (Joyce, Woolf, Lawrence, etc.). Their work was obtuse, rarefied, elitist; Kingsley simply wanted to tell funny stories about ordinary people. Martin took his lead from Modernism rather than from his father, preferring ornate, virtuosic language to Kingsley’s plain style, and post-modern tricksiness and self-referentiality to his immersive realism. When questioned about Kingsley’s dismissal of this kind of writing as “Fucking Around with the Reader” in Rolling Stone, Martin described it as an “evolutionary development” of the novel and said that his father was “in the position of someone in fifteenth-century Venice or Florence saying: ‘You know, I don’t like this perspective stuff. Get back to when we didn’t know about perspective.’ Despite their differences, however, as the novelist Julian Barnes has said, ‘They do love each other.”

FAMOUS SAYINGS

Kinsley

“Nice things are nicer than nasty ones.”

“If you can’t annoy somebody there is little point in writing.”

“It is no wonder that people are so horrible when they start their life as children.”

Martin

“Laughter always forgives.”

“Sexism is like racism: we all feel such impulses.”

“Good sex is impossible to write about… It may be that good sex is something fiction just can't do — like dreams. Most of the sex in my novels is absolutely disastrous. Sex can be funny, but not very sexy.”

WHAT DID THEY BELIEVE?

Kingsley

Kingsley belonged to a generation of young, English, male writers who were popularly known – much to their dismay – as Angry Young Men. They were mainly working and middle class, disillusioned men who saw English life as stifling and boring. They questioned all orthodoxies and, in the words of the writer Christopher Hitchens, waged a “protracted war against hypocrisy and phoniness of all kinds”. Like most Angry Young Men, Kingsley Amis began his political life on the Left – in the 1950s he claimed he would always vote Labour, and was even a member of the Communist Party at university – but moved to the Right as he grew older.

Kingsley was also a member of a group of writers known as ‘The Movement’, who saw England as increasingly irrelevant in world affairs – World War Two was over; Empire was a thing of the past – and mourned the loss of a traditional English lifestyle. England, for writers like Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis, was a lost Eden concreted over by a banal and exploitative urban lifestyle.

Martin

For Martin, the most important thing for a writer to do is to avoid cliché. In an essay on James Joyce, he wrote: “To idealise: all writing is a campaign against cliché. Not just clichés of the pen but clichés of the mind and clichés of the heart.” Writing, for him, is a chance to think freshly about things, to see the world in a new light, and reconsider one’s assumptions. The late 20th century, for Martin, was full of people not thinking freshly, not questioning their assumptions, but following a new, capitalist orthodoxy, a worldview which conflated money with democracy and held that the richer you are the freer you are. This worldview, in Martin’s writing, is signaled by “the brash ascendancy of tabloid England, the downmarket world of Page Three pinups, Bingo greed and soap stars' abortions,” to quote Mira Stout in the New York Times. In his own words: “Money is a more democratic medium than blood, but money as a cultural banner - you can feel the whole of society deteriorating around you because of that. Civility, civilisation is falling apart.”

WHO WOULD BE MOST FUN AT DINNER?

Kinsley

“Now and then I become conscious,” Kingsley wrote in his memoir, “of having the reputation of being one of the great drinkers, if not one of the great drunks, of our time.” His sharp wit, erudition and drunken bonhomie would, no doubt, make him an excellent dinner companion. But you’d better watch out: he might try to sleep with you. He was a serial adulterer who made no attempt to hide it from his wife. The writer Al Alvarez tells an anecdote about a drunken dinner the Amis’s once hosted during which Kingsley disappeared, one by one, with every woman present. "What got to me most about the whole performance,” Alvarez said, “was that everyone was miserable — the women who went outside with Kingsley, as much as those who were left behind, even Kingsley himself — but nobody said a word.”

Martin

Martin drank less, adulterated less – but you could be sure he’d say something memorably outrageous. He once, for example, called for the installation of “suicide booths” on street corners so that the elderly could quietly end their lives in comfort. He is perhaps most outspoken when talking about writers of enormous stature. In his memoir Experience, he relates a dinner party at which the Indian novelist Salmon Rushdie asked him to step outside for a fight after he insulted Samuel Beckett’s prose. The novelist Will Self remembers another dinner party at which Amis rolled around on the floor, frothing at the mouth, in anger the Nobel-Prize-and-Twice-Booker-Prize-winning South African Novelist J.M. Coetzee’s use of cliché.

WHAT DO THE CRITICS THINK?

Kingsley

No-one would question Christopher Hitchens’s assertion that Lucky Jim is “the funniest book of the last half century”. The Guardian called it “preposterously funny”, Helene Dunmore, ‘a flawless comic novel’. Or as John Mortimer had it, ‘He was a genuine comic writer, probably the best after P. G. Wodehouse”. Those who criticise him tend to focus on his latent misogyny. They may have a point: he once wrote in a letter to the poet Philip Larkin: “Women appear to me as basically dull but as basically pathetic too.”

Martin

The Sunday Independent has called him “the finest English fiction writer of his generation”, A.O. Scott has called him ‘the best American writer England has ever produced’ and John Sutherland has called him “the most daring novelist of his generation”. However, Martin has received his fair share of memorably bad reviews. Tibor Fischer, for example, said of his novel Yellow Dog: “Yellow Dog isn't bad as in not very good or slightly disappointing. It's not-knowing-where-to-look bad. I was reading my copy on the Tube and I was terrified someone would look over my shoulder… It's like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating.”

HOW SUCCESSFUL WERE THEY

Kinsley

According to a list published in the Times in 2008, Kingsley Amis is the 9th greatest British writer since 1945. Lucky Jim was listed in TIME’s list of the 100 greatest novels since 1923. By the 1970s it had sold over 1,250,000 copies in America alone. Though he never quite matched this early success, he went on to write 27 further novels, none of which were flops – not to mention countless books of essays, poems, etc.

Martin

Martin ranked lower than his father in the Times’s list: he is apparently the 19th greatest British writer since 1945. But his novel, Money was also listed in TIME’s list of the 100 greatest novels. He has not outsold his father, but has done better than him in one respect: for his 1995 novel The Information he received an advance of £500,000 – an unprecedented sum for a literary novel.

WHO HAS THE BEST WAY WITH WORDS?

Kinsley

Kingsley’s prose is simple, uncomplicated. As the critic Rubin Rabinowitz has said of his novels, “their styles are plain, their time-sequences are chronological, and they make no use of myth, symbol or stream-of-consciousness inner narratives”. But his writing is marked by impeccable comic timing and joyfully unexpected phrasing, as in this memorable description of a hangover in Lucky Jim: “His mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum. During the night, too, he’d somehow been on a cross-country run and then been expertly beaten up by secret police.”

Martin

If Kinglsey’s prose is notable for its plainness, his son’s is notable for its elaborateness. As the novelist Sebastian Faulks has said: “When the father was happy to write “Dixon paid the garage-man and the taxi moved off,” as though challenging the reader to see how his meaning could have been more clearly conveyed, the son seemed reluctant to pass any sentence in which words were not pressed hard against one another to produce unsettling effects.” Here, for example, is a description of arriving in America in Money: “So now I stand here with my case, in smiting light and island rain. Behind me massed water looms, and the industrial corsetry of FDR Drive... It must be pushing eight o’clock by now but the weepy breath of the day still shields its glow, a guttering glow, very wretched – rained on, leaked on.”